About a year ago, I discovered some software called TrainerRoad. TrainerRoad is cycling training software that creates power-based workouts by combining sensor data from your bike with your home computer. I first tried this software last April, and really liked it. At the time, I did not have a power meter on my bike, so I used something that TrainerRoad calls "VirtualPower". "VirtualPower" estimates your power output based on your speed from your speed sensor along with known data for the particular indoor trainer that you are using. Training based on power is supposed to be better than training just based on heart-rate, so it seemed like a good plan.

TrainerRoad includes hundreds of pre-programmed workouts, and also allows you to create your own. Because I had been using Spinervals videos, I decided to create some power-based workouts in TrainerRoad that could be sync'd with the Spinervals videos. Fortunately, some users had already done a lot of that, but I found that I needed to create others. Soon, there was a pretty good collection of power workouts to go along with the Spinervals videos. I ended up doing that for most of last year.

But I still felt like I was missing something. "VirtualPower" was OK, but definitely has some drawbacks. Because it is estimating power based on other data, rather than measuring power directly, other factors can affect the power number. For example, if your trainer tension is a little different from workout to workout. Or if your tire pressure changes. These factors change the relationship of the trainer to the bike, changing the perceived power output. A way to avoid this inconsistency is to just install a true power meter on the bike.

So, I really wanted to get a power meter. Big downside: power meters are very expensive. Big upside: everything else. So, I decided it just needed to happen. And I had just gotten a new bike (more on that in another post), and I decided that I just had to make the power meter happen. After looking at a number of options, I opted to get a Power2Max power meter. This power meter is installed on my front chainring, and measures minute stresses transferred from the cranks to the chainring, and converts that into a power measurement, measured in watts. Therefore, it is truly measuring the pressure I am putting into the bike. There are other ways to measure this, too, all involving some kind of "strain gauge" somewhere on the bike. This could be in the rear hub, on the crank arms, or directly on the pedals themselves.

Here is a quick breakdown on power meter locations, and my opinions on the pros and cons of each:

- Rear hub:

- Pros:

- Relatively inexpensive

- Because it is part of the wheel, your power meter can be easily moved between bikes just by swapping wheels. I only have one bike for training and racing, so this wasn't a big factor for me.

- Cons:

- Limits you to one wheel option to measure power. If you train and race on different wheels, like I do, this isn't really feasible.

- Crank arm:

- Pros:

- Cheapest option out there these days

- Extremely lightweight.

- Cons:

- Generally limited to specific crank arms. You typically buy the crank arm from the power meter manufacturer with the power meter already installed.

- Limited to crank arms with a smooth inside face that the power meter can be installed onto. In my case, I am using Rotor-brand cranks, which have a shaped inside face that won't accept this type of power meter. I like my cranks, and didn't really want to spend extra money buying a full set of cranks, too.

- Pedals:

- Pros:

- Easy to measure directly left/right power by having one power meter in each pedal. Most other options have to estimate left/right power balance using various calculations. This wasn't too important to me.

- Easily swapped between bikes, just by swapping pedals.

- Cons:

- Significantly more expensive than the other options.

- Chainrings:

- Pros:

- Depending on the manufacturer, this can range from one of the least expensive options, to one of the most expensive. The cheaper options are about $800, and the more expensive can be a couple thousand dollars.

- Cons:

- A little complicated to install. Probably easier to take to a shop, where they can do it quickly, easily, and relatively inexpensively.

- Can't be swapped between bikes. With only one bike, this wasn't a big deal to me.

|

| My Power2Max power meter installed. The power meter itself is the thing with the big "2" on it. You can also see my Praxis chainrings and Rotor 3D cranks. |

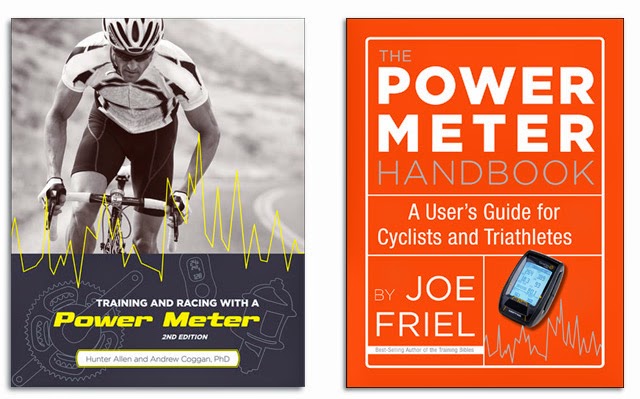

The next step was understanding how to use power-based training. To do that, I relied on a couple books. I won't try to describe everything here, since other people can teach power-based training much better than I can. These two books taught me everything I needed to know about training with power: Training and Racing with a Power Meter by Hunter Allen and Andrew Coggan, considered the bible of power-based training, and The Power Meter Handbook by Joe Friel, another excellent book, and an easier read than the Allen/Coggan book.

|

| Some of the best power-training books out there. Read them. |

Now that I had the power meter installed, and had a basic understanding of power-based training, it was time to get to work. Back in November, I had the power meter installed just in time for the second phase of my Spinervals off-season training program. The first phase was a lot of base training, for 6 weeks. The second phase of their program lasts the entire month of December, and is a solid month of hard base training. Similar workouts to the first phase, but just more volume. I continued to use the Spinervals videos sync'd with TrainerRoad software, but now I could use actual power numbers. The difference was significant.

With VirtualPower, I was never sure that I was doing equivalent work every time I got on the bike, because I wasn't sure if my trainer had the same tension, or if my tire pressure was the same as the previous day. With true power measurements, that was no longer an issue. If something changed in my setup, that just meant I had to pedal a little faster or slower, or use a different gear, to achieve the power output necessary per the workout. I continued to train this way throughout December.

After finishing the December phase of the workout, it was time to move to the next phase. But at this time, I started having second thoughts about Spinervals. Although they are great workouts, I felt I was missing something. The Spinervals off-season training plan is somewhat generic, with the same free training plan available for anyone who wants to use it, regardless of their goals. It involves a lot of volume, and a lot of hard work, but I don't know that it really focuses on what I need. After using the videos for a few years, it really started to seem to me like they were focused more on the needs of triathletes, not road races. There are hard workouts, to be sure, but most seemed geared towards long, strenuous work needed for time trials and triathlons, but not the on/off demands needed for road racing, where you need to be able to perform breakaways, catch breakaways, and sprint out of corners and for the finish line. With nearly 50 videos, there were certainly some workouts that focused on high intensity intervals, but most workouts were based on long, steady hard work. The free training plan certainly seemed focused on this.

The other problem with Spinervals workouts is that they were created just as video workouts, usually focused on heart-rate training. In order to use them as power-based workouts, I would use TrainerRoad with either a premade workout, or make my own. These workouts were all user-created, and not provided by Spinervals. The user would open a video, and open the TrainerRoad workout creator, and create intervals that started and stopped in sync with the video, and would have to guess at the amount of power that should be expected for that interval based on things the Coach was talking about. This wasn't necessarily ideal.

I eventually decided I might need to try something else, based completely on power. TrainerRoad includes over 400 workouts of all varying intensity, duration and type of work. And as part of the subscription, they also offer a variety of training plans. At the time I considering the change, TrainerRoad was also reorganizing their training plans to make sure they were covering everyone's needs. And based on what they were doing, they were definitely going to provide exactly what I was looking for, right when I needed it.

Around the beginning of 2015, TrainerRoad changed their training plans to provide three distinct phases: Base, Build and Specialty. There are a number of options within these phases to allow you to build the plan that meets your specific needs. And each options is also broken out into low, medium and high volume options, so you can work within your specific time constraints.

- The Base phases are generally all 12 weeks in length. They offer Sweet Spot and Traditional base plans, depending on how much time you have and how thorough the plan needs to be.

- The Build plans are 8 weeks, and broken out by Short Power (mountain biking, cyclocross, criterium racers), General (road racers), and Sustained Power (triathletes, TT specialists, century riders).

- The Specialty phase plans are really topping-off plans, as a final 8-weeks of work to get you in peak condition for your specific type of event. These are broken first into Road, Off-Road, Triathlon, and General Fitness options, and then there are further options within each of those categories. For example, the Road category includes Rolling Road Race, Climbing Road Race, Criterium, 40k TT, Half Century and Century plans. I understand they also intend to offer a Stage Race plan as well.

To plan my schedule, I needed to determine my goal events for the year, also known as my "A" races. I decided that these would be the Superior Morgul Omnium in May and the Salida Stage Race in July. Both are three-day races that I feel I could to fairly well at. So my goal was to be in top form for both of these races. To do that, I would need to complete the Specialty phase a week or two before the event, so I could taper and be at a top level of fitness, with a low level of fatigue. So, got out my calendar and counted backwards 17 weeks from the Superior Morgul race, so I could determine when to start my Build phase. That would give me 8 weeks of Build, 8 weeks of Specialty, and one week of taper. Based on that calculation, I began my Build phase in the middle of January.

Now here I am in the middle of March. I completed my Build phase, and am now a couple weeks into my Rolling Road Race plan. A typical week for me consists of six days of workouts.

- Monday: Rest day

- Tuesday: 60 minutes of hard intervals, focusing on some specific type of power output

- Wednesday: 60 minutes of mellow Zone 2 or Zone 3 riding

- Thursday: Another 60 minutes of hard intervals.

- Friday: Another 60 minutes of Zone 2/3

- Saturday: 90 minutes of hard intervals. If I am able, I may join a hard group ride instead, to get some race-type experience in my legs.

- Sunday: Long-ish 2.5 - 3 hours of Zone 2-3 work, just to work on endurance.

As I said, TrainerRoad workouts are based on power. The software pulls my heart rate, power and cadence from my bike's sensors and displays them on a "dashboard", along with target power and a graph of the entire workout. As I ride, I aim to hit the power targets as directed per the workout. Once I am done, the workout is saved, and I can review my performance data. In a future post, I will talk about how I use my workout data as a part of my overall training plan.

|

| This is a TrainerRoad post-workout graph. The blue is the target power. The yellow line is my actual power, red line is my heart rate and white line is my cadence. |

I'm pretty sure this is my longest post ever. It seems like I could keep writing about this stuff forever, but I'll have to save some for other posts. Until next time . . .

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave me a message!